Outputs

Filter by type

Filter by work packages

document

V-Data final conference

Final conference

The final conference of the project “V-Data - The value of digital data: enhancing citizens’ awareness and voice about surveillance capitalism”, funded by Fondazione Cariplo, will take place 7-8 September 2023 at the University of Pavia (https://web-en.unipv.it/about-us/), Department of Political and Social Sciences, Italy. The event will comprise panel presentations and one keynote session hosting the internationally renowned scholar Stefania Milan (https://www.stefaniamilan.net/about-me/). A maximum of 25 papers will be selected for presentation. Preference will be given to speakers who plan to attend the conference in person, but a small number of remote presentations (no more than one per panel) may be included in the programme. The organising committee is exploring options to publish a special issue in a peer review journal associated with this call for contributions.

Call for contributions

DEADLINE EXTENDED: the deadline for sending your contributions has been extended until 12 May 2023! We invite researchers who are active in the field of surveillance capitalism, data justice, algorithmic studies, data ethics, Science and Technology Studies (STS), digital and computational methods, digital labour, media consumption and attitudes, critical consumer studies, platform studies (and many more) to submit proposals for paper presentations. Please submit an abstract (max. 300 words) to the event organisers by sending it via email to vdataresearch@gmail.com by 12 May 2023.

The conference theme is The value of digital data: advancing empirical research on surveillance capitalism. We encourage proposals from researchers with a variety of backgrounds, including academic research, activism, marketing research, journalists, and government social research. The following are examples of topics that are of particular interest:

- Public opinion and awareness about processes of data extraction, appropriation, and valorisation.

- Emic conceptions of data value: surveillance capitalism imaginaries across socio-economic groups, cultures, ethnicities, age cohorts, and geographies.

- Consumer practices of resistance, compliance and negotiation towards vocal assistants, targeted advertising, algorithmic systems of recommendation, AI devices (etc.).

- The nexus between Covid-19 pandemic and surveillance capitalism.

- Digital labour exploitation in surveillance capitalism (or surreptitious strategies of data appropriation).

- Working in the data factory (e.g., data cleaning, moderation, data entry, etc.).

- Innovative methods for studying surveillance capitalism.

- Digital and computational methods for studying surveillance capitalism (or how to surveille the surveillants).

- Survey methods for studying surveillance capitalism.

- Making surveillance capitalism visible through data visualisation (and other visual aids).

- Arts and surveillance capitalism imaginaries.

- Utopian and dystopian imaginaries of surveillance capitalism.

- Data activism and surveillance capitalism.

- Surveillance capitalism in the Global South.

- Big data and finance.

- Discrimination, inequalities and injustice related to processes of surveillance capitalism.

- How does the concept of data value change according to different stakeholders (consumers, marketers, brands, analysts, etc.) as well as market segments (e.g. automotive, food, fashion, etc.)?

- Big data consumer profiling and implication on identity and subjectivity.

- How digital affordances shape imaginaries of and practices related to surveillance capitalism.

- The platformization of consumer imagination and practices (or how platforms standardise consumer behaviours to make them more predictable and data-ready).

- Living with the hyper-nudging.

Conference venue

The conference will take place at the University of Pavia (https://web-en.unipv.it/about-us/), Department of Political and Social Sciences, Italy. Pavia is located 30 km south of Milan, to which is connected by trains every 30 minutes.

Important dates

Abstracts are due by 12 May 2023. These should include the author(s) name and position, a short title, and a clear indication of whether they plan to attend the conference in person or remotely. Acceptance notices will be given by 31 May 2023.

Fees and Accommodation

The event fee is 80 Euros. Fee includes: a) welcome package; b) daily lunches and coffee break; c) social dinner. The fee does not include accommodation. Anyway, for those interested the Department provides up to 15 single rooms at a convenient rate of euros 49 by the University dorms. Participants who are interested in staying at the University dorms must mention it in their submission. Priority in the allocation of rooms will be given to early-career scholars and according to submission date.

Organising committee

Alessandro Caliandro, Flavio Ceravolo, Guido Legnante, Samantha Conte, Antonella Orologiaio, Susanna Sassi (Università di Pavia), Emma Garavaglia (Politecnico di Milano), Alessandra Gaia (Università degli Studi di Milano-Bicocca), Dario Pizzul (Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore).

Conference programme

Thursday, September 7th

- 10:00 AM: Registration opens

- 11:00 AM - 12:00 PM: Welcome and openings

- 12:00 PM - 1:00 PM: Light Lunch

1:00 PM - 3:00 PM

Session 1 - Resistance & Countersurveillance (Aula B) - Chair: Veronica Moretti

- Lucio Pereira Mello: Battle for platform regulation in Brazil: mapping data as political strategy

- John Boy: Practical Rejections of Surveillance Capitalist Platforms and Their Directions

- Matteo Adamoli and Tiziana Piccioni: Practices of resistance in digital third spaces: critical aspects of the platformisation during the pandemic in high education

- Milana Pisarić: Digital Surveillance State vs. Digital Privacy Rights

Session 2 – Theory (Aula Grande) - Chair: Alessandro Caliandro

- Gianmarco Cristofari: A comparative historical account of value production inside digital platforms

- Adam Arvidsson: The Question of the Digital in the Anthropocene

- Dario Pizzul and Alessandro Caliandro: A systematic literature review of surveillance capitalism: towards an empirical research agenda

- Guido Anselmi: Yet another round of disruption: the imaginary of LLMs in social and legacy media

3:00 PM - 3:30 PM: Break

3:30 PM - 4:30 PM: Keynote Speech (Aula Grande) Stefania Milan (Professor of Critical Data Studies at the University of Amsterdam)

4:30 PM - 6:30 PM

Session 3 – Awareness (Aula B) - Chair: Marco Gui

- Martin Trans: Datafying groceries: consumers’ willingness to participate in loyalty programs

- Margherita Bordignon, Guido Legnante, Chiara Respi, Marco Gui and Dario Pizzul: The price is right: exploring the economic value of personal data among Italian citizens

- Riccardo Pronzato: The reproduction of hegemony in youth’s everyday platform engagements

- Chiara Respi, Marco Gui, Guido Legnante, Dario Pizzul, Tiziano Gerosa, Gaetano Scaduto and Miriam Serini: Privacy protection as an exception in the digital inequality framework (and why this is not good news)

Session 4 - Geographical contexts (Aula Grande) - Chair: Guido Legnante

- Salvatore Romano, Davide Beraldo and Ilir Rama: The Impact of TikTok Policies on Information Flows during Times of War: Evidence of ‘Splinternet’ and ‘Shadow-Promotion’ in Russia

- Susanna Sassi and Guido Legnante: How media and journalism represent surveillance capitalism in Italy

- Claudio Bellinzona: The future of smart cities in the context of surveillance capitalism. The case of Dubai

- Isabela Rosal Santos: The regulation of data brokers in Europe: solutions presented by the new regulations

7:30 PM: Social dinner “Horti” - Lungo Ticino Sforza, 46, 27100 Pavia

Friday, September 8th

9:00 AM - 11:00 AM

Session 5 – Activism (Aula B) - Chair: Alessandro Caliandro

- Alice di Leva, Emma Garavaglia and Annavittoria Sarli: Social injustice in surveillance capitalism: reflections on the Italian context

- Annika Richterich: Who values Data Minimalism? On Solidarity in Feminist Data Activism

- Peter Mechant, Sander Van Damme, Marteen de Mildt, Steven Dewaele, and Laurens Vandercruysse: Personal Data Stores and data cooperatives: a two-pronged, sociotechnical approach for data activism

- Michele Veneziano: Monitoring public administrations to fight surveillance capitalism: Practices and imaginaries of an Italian tech watchdog

Session 6 – Algorithms (Aula Grande) - Chair: Dario Pizzul

- Massimo Airoldi and Tiziano Bonini: Capturing habitus: how algorithms extract value from platformized culture

- Natalia Stanusch: Memeing Algorithmic Imaginaries: How Users Fight against and Comply with Recommendation Algorithms Using Data

- Davide Beraldo, Massimo Airoldi, Sander van Haperen and Stefania Milan: Algorithms as Cultural Objects: mapping algorithmic imaginaries on Twitter

- Luca Giuffrè: Algorithm Literacy at School: teenagers reasoning of algorithm-mediated experiences

11:00 AM - 11:30 AM: Coffee break

11:30 AM - 1:00 PM

Session 7 – Work and cultural production (Aula B) - Chair: Natalia Stanusch

- Alessandro Gandini, Marianna d’Ovidio and Ilir Rama: Community, cultural production and the pandemic

- Josephine West: Sex, Power and Surveillance Capitalism in the Multi-Billion Dollar Camming Sector

- Emma Garavaglia, Annavittoria Sarli and Francesco Diodati: Carework platforms in Italy: a qualitative research

Session 8 - Family & parenting (Aula Grande) - Chair: Alessandro Caliandro

- Julie Dereymaeker, Tom De Leyn and Ralf De Wolf: Datafied families and parental surveillance by default? Exploring parental care and surveillance in the construction of smart home technology

- Ribak Rivka and Gal Shayovitz: Surveillance Capitalism In Embryo

- Mathias Klang: Parental Panopticons and Everyday Resistance: Domestic Surveillance and young adults

document

Documenti Privacy

Da qui è possibile accedere a due interessanti documenti, pensati per docenti e studenti, utili per saperne di più sulle leggi italiane che tutelano privacy e reputazione online.

Privacy per educatori

Una risorsa per insegnanti ed educatori che vogliano saperne di più sulle basi giuridiche della gestione della privacy e dei dati online, così da supportare le più giovani e i più giovani nell’utilizzo degli strumenti digitali.

Privacy per studenti

Una risorsa che aiuta le più giovani e i più giovani a comprendere le fondamenta ed il funzionamento delle leggi che proteggono la nostra privacy e reputazione online.

document

Italian experts’ perspective on social justice issues linked to surveillance capitalism practices

Introduction

In an economy predominantly driven by the exploitation of information sources, such as surveillance capitalism, power is in the hands of those who can manage this information. Therefore, the whole system relies on the unbalance between those subjected to exploitation and those who manage the data: this unbalance potentially creates or perpetuates social injustice. Among the most extensively researched disparities within surveillance capitalism are related to privacy issues. However, there are other serious potential social harms associated with the conventional practices of surveillance capitalism. For instance, scholars have begun to examine potential discriminatory and exclusionary threats that may arise due to the extensive utilization of data, but this area of study still requires significant development. Our study aims at contributing to the reflection on social justice issues related to surveillance capitalism practices, other than privacy. We focus on the Italian context, still an understudied case. The study has so far entailed the organization of 3 online focus groups (March and April 2023) with 11 total participants (both digital activists and experts). The main themes for discussion proposed in the sessions were the following: social injustice linked to surveillance capitalism processes; specific social, cultural or economic characteristics of the Italian context in relation to the theme; resistance practices in the Italian context.

The research question guiding our work is: Which are the specificities of the Italian context that can constitute a breeding ground for the potential harms deriving from surveillance capitalism practices?

Insights derived from our conversations with activists and experts show that, at the moment, Italy is far from having the conditions allowing to prevent and contrast the possible harms of surveillance capitalism processes. The themes around which the participants’ narration about this general issue has focused are now discussed more in detail. Overall, it is interesting to note that the aspects emerged and discussed during focus groups are not specifically linked to the economic aspects of surveillance capitalism (i.e.: the appropriation of economic value, without redistribution): these aspects seem much more invisible and difficult to ‘visualize’ and ‘verbalize’ even for experts.

Theme 1 - Lack of awareness and debate

Participants lamented the absence of informed, specialized and professional public and political debate on the topic of surveillance capitalism and its potential harms: Whenever European privacy issues came up, or for example we make a big petition, we make a European campaign on this issue, on illicit data collection, the Italian team always said: no, in Italy they don’t give a shit to anyone. We don’t do these campaigns. We tried, but no one signed it, it was a matter not heard, not relevant.

The complete lack of a shared discussion, involving various kinds of institutions and citizens, about issues of social injustice related to the collection and use of personal data by digital platforms – and actually, more in general, about surveillance capitalism – is considered an important obstacle to the capacity of preventing and contrasting existing risks.

It is interesting to notice that, even experts participating to our focus groups, more readily refer to the concept of privacy when discussing harms of surveillance capitalism.

Furthermore, participants recognised scarce digital literacy within the population (in general, and especially among certain groups – e.g. low educated groups) and linked this to a reduced awareness about the potential harms of surveillance capitalism in terms of social injustice: Specifically, to the Italian case there is no algorithmic awareness and awareness of the platforms, in the sense that even when we talk about online violence, but any other online phenomenon, there is no awareness of the mediation that takes place through the platform, so we tend to talk about these phenomena as if they were equal to those that occur in offline environments.

Last, but not least, participants recognised a general collusion of Italian citizens with surveillance practices acted by private digital platforms versus a tendency to consider unacceptable surveillance through digital devices acted by the State: This is an ideological issue: I trust Facebook to take my data, but I don’t trust the state to take my data. This was even more manifest, with some digital entrepreneurs, startuppers, people who should have some data awareness… they impersonate anarcho-liberal ideology, and this was consonant with the whole part, no vax, no greenpass, triggered by anti-State feelings.

Themes 2 - Homophobia, racism, sexism

A second key issue emerged from the discussion about the potential harms of surveillance capitalism processes in terms of social injustice is related to harmful online behaviors directed towards vulnerable groups. Participants’ narration tended to link them to a (offline) culture still permeated by homophobia, racism and sexism and a context in which an adequate institutional presence and action, both in terms of prevention and support to the victims is still lacking: If we look at the Italian political culture, there are some peculiarities that then reproduce in the way technology is imagined and innovation is how resistance is imagined. In my opinion, at the level of the citizen and consequently of the media, there is already a low sensitivity towards discrimination, human rights, Italy always lags a little behind. […] lot of people do things on Internet because they think they’ll go unpunished. In Italy we have this vision: I can do what I want on Internet. Not only against others, but also about myself

Theme 3 – “Traditional” technology culture

A third question around which participants’ discussions converged regards the technological culture typical of our Country. The Italian context seems to be characterized by a cult of technological innovation for entrepreneurial progress. In a system made by small and medium enterprises the discussion around technological innovation tends to be monopolized by a positive vision that relates it to economic progress. Any critical reflection on issues of digitalization, technology, innovation tends to be seen as an obstacle to the opportunity for Italy to (finally) catching up with what most advanced economic systems are doing: In Italy we have the fear of lagging behind in the field of technology, so anything that can block innovation can be seen badly. When the Garante della Privacy says something, then everyone reacts “eh but then we cannot do anything”, small businesses, e-commerce, because we already feel like we have fallen behind, so if something blocks us it seems that it is something that penalizes us.

Moreover, if technology and technological innovation are often discussed in relation to economic growth, the potential of innovation – and specifically of big data – for social good is very rarely debated in public and political contexts: It’s difficult to have intercommunication and therefore connection between the various databases, which, in my opinion, it is a fundamental thing because on the one hand it is risky, but on the other it is powerful because if we have a public monitoring of the health connections of citizens we can see when circumstances happen. Classic example: Taranto. How many cancers there are, how much pollution? What big companies do: predict what is a trend. The public should do this, talking about territorial health.

| Themes | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Lack of awareness and debate | Public debate Political debate Scientific knowledge Digital literacy Awareness |

| Homophobia, racism, sexism | Culture Vulnerable groups Institutions Prevention Protection |

| Traditional technology culture | SMEs Innovation Technological culture Public goods |

document

Research Centres and Initiatives

Hereby a useful directory of Initiatives and Research Centres working on several issues and topics related to surveillance capitalism (such as dataveillance, data activism, data ethics, data privacy & transparency, platform surveillance, etc.)

Open the spreadsheet and contact us if you want to contribute to the list.

document

Come resistere (per quanto possibile) al capitalismo della sorveglianza

Da qui è possibile accedere ad un interessante report di ricerca che introduce e descrive diverse pratiche tecno-sociali di resistenza al capitalismo della sorveglianza – utili a chiunque, non solo intenda saperne di più circa l’argomento, ma voglia anche provare (per quanto possibile) ad opporvisi. Il report, infatti, descrive una lunga serie di pratiche digitali quotidiane utili a limitare gli effetti del capitalismo della sorveglianza sugli individui e sulla società nel suo complesso.

Tali pratiche vengono raggruppate in 4 macro-categorie principali (che si distinguono per crescenti gradi di sforzo e competenze richieste all’individuo per poter essere messe in atto):

a. le buone abitudini;

b. riprendere il controllo;

c. il camuffamento;

d. l’attivismo.

Al di là dei suoi risvolti pratici, il report si rivela anche utile per mettere in prospettiva alcuni discorsi di marketing, entrati ormai nell’immaginario comune, che vorrebbero privacy e data protection come concetti dati per ‘morti’, ormai obsoleti nell’odierna società digitale e di scarso interesse per il grande pubblico. Viceversa, come dimostra il report, non solo gli utenti comuni hanno a disposizioni una vasta pletora di strumenti e strategie per resistere al capitalismo della sorveglianza, ma anche che tali strumenti e strategie sono largamente praticati da ampie fasce della popolazione (es., si veda il crescente ricorso che gli utenti fatto di AdBlocker e VPN).

document

Rotterdam Conference

Hereby the slides that we presented at the 2022 Surveillance & Society Rotterdam Conference. Each set of slides is accompanied by the related abstract.

A systematic literature review of surveillance capitalism towards a research agenda

Although surveillance capitalism - as intended by Shoshana Zuboff - is an emerging topic, it already attracted the attention of many scholars from different fields within social sciences. Therefore, in this contribution we propose a systematic literature review of the topic of surveillance capitalism. Specifically, we developed a systematic literature review on a pool of 161 academic articles automatically extracted (through a Python script) from ad hoc scientific sources (e.g., Scopus), which we processed with computational techniques of text analysis (e.g., co-word analysis, topic modelling, TF-IDF). Also, a close reading of a sample of 30 articles was conducted. Results show that the topic of surveillance capitalism is composed by six main sub-topics: marketing & social control, big data & datafication, platforms & platformization, data privacy & protection, culture of surveillance, AI. We argue that all these key sub-topics need to be addressed attentively (or at least taken into consideration) when dealing with academic research and/or writing on surveillance capitalism, also paying attention on how each dimension inform and co-construct each other.

Mapping the culture of surveillance capitalism on Twitter

Although surveillance capitalism is already well-established in advanced economies, we can argue that the current Covid-19 emergence has probably accelerate the diffusion of surveillance capitalism logics and infrastructures (e.g., platformization of higher education). Despite the pervasiveness and currency of this phenomenon, we still know very little about how the general public perceives and frames it. In particular, there is a shortage of empirical research on citizens’ opinions towards surveillance capitalism as well as their level of awareness about the processes of data exploitation and value extraction carried out by corporate platforms on the very data users produce through their everyday digital practices. To address this research gap, we developed an exploration (based on digital methods) on dataset of 302k Italian tweets (collected by following ad hoc keywords, such as ‘surveillance + Facebook’, ‘surveillance + iPhone’, etc). We analyzed this dataset combining computational and qualitative techniques – network analysis, topic modelling, ethnographic content analysis. Our preliminary results show that, on a general level, Twitter users seem unable to distinguish between processes of surveillance upon citizens and consumers (which they consider basically the same thing). Anyhow, on a micro level, specific communities of users tend to develop different narratives on surveillance capitalism, imagining different ‘models’ of it (such as, dystopian surveillance, benevolent surveillance, conspiracy surveillance, entertainment surveillance).

Algorithmic countersurveillance Immuni on Reddit

This research proposes a reflection on the implications of dataveillance (based on algorithms) and practices of countersurveillance in the healthcare field. Countersurveillance is the practice of making surveillance activities of institutions difficult or implementing technologies to evade surveillance altogether. Countersurveillance achieves its goal by subverting various components of the surveillance process and it has many applications. It can be used to protect privacy, civil liberties, and against abuses of surveillance. Additionally, it may be employed to push surveillance systems beyond their breaking point and in doing so it identifies potential vulnerabilities and points of error. Many countersurveillance techniques use human methods rather than electronic; these activities might include ‘evasion’ (e.g., avoiding risky locations, being discreet or using code words), ‘being situation-aware’; ‘hiding in secure locations’; and ‘concealing one’s identity’. Through this proposal we want to explore resistance practices and imaginaries applied to algorithmic surveillance in the health domain. Specifically, we explore the debate on the Immuni App on Reddit.

document

Visualizing Italian citizens’ trust and worries about digital platforms through survey data

Introduction

More and more people are used to (consciously or unconsciously) “leave traces” of their personal data when surfing the Internet, logging into apps and websites, buying services and products online, etc. However there is little knowledge on trust that people put in the actors who handle digital data, and on their attitudes towards processes of digital data exploitation for business and non-business purposes. To address these topics, we carried out the survey “The citizens and the value of digital data” (N=3,156). We administered the questionnaire to a quota sample of the Italian Internet population (aged 18 and above), adopting a mixed-mode design: a CAWI survey on respondents from the Opinione.net non-probability online panel (N=2,249), followed by a CATI survey on respondents who have a phone number (both landline and mobile), own/have at their disposal at least one digital device, and use at least three features offered by the digital devices (N=907). The questionnaire includes various sections on different topics, such as ownership and frequency of use of digital devices, awareness about how and to which aims digital data are extracted and exploited, data sharing behaviors, the economic value that personal digital data produce, attitudes towards online data protection, etc. Here we focus on results regarding trust in the digital companies and (potential) worries about how some actors manage people’s digital data.

Output 1

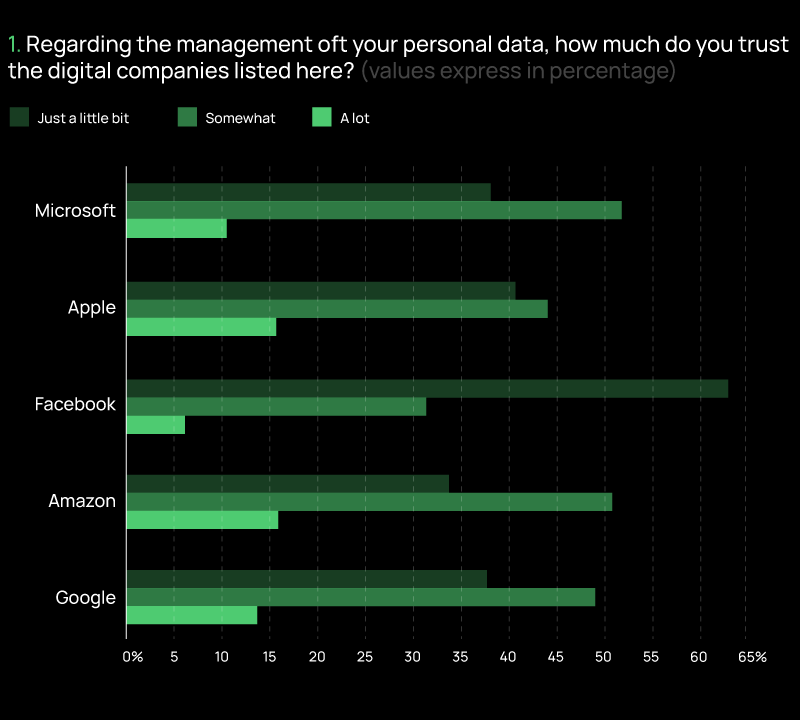

We asked respondents to indicate their level of trust in the GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, and Microsoft) companies, selecting from “just a little trust”, “somewhat trust” or “a lot trust”. Overall, putting GAFAM together in a trust index (range from 0 to 10), the mean value of respondents’ trust in digital companies is 3.4.

Output 2

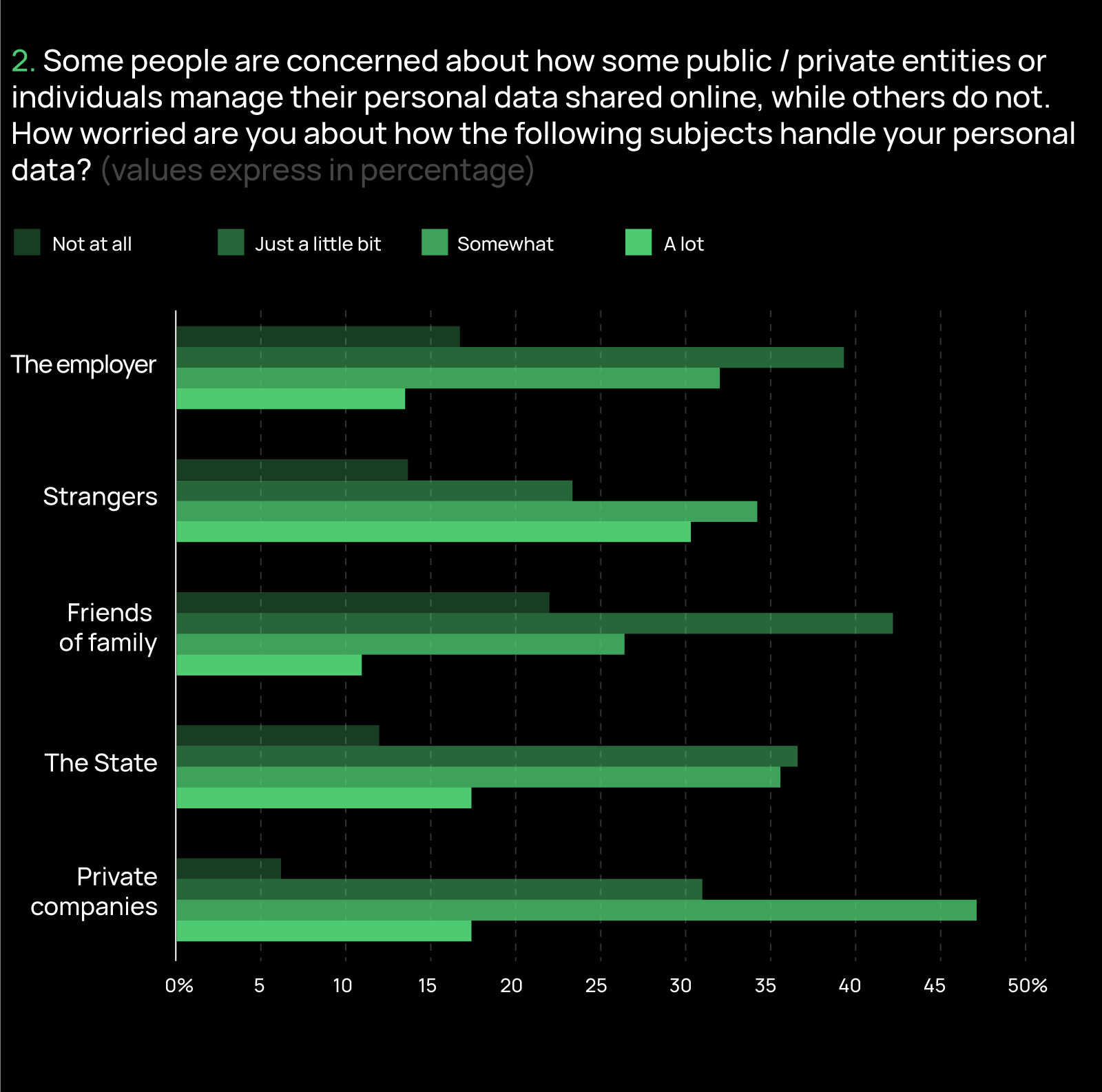

We then tried to investigate if people’s attitudes go beyond the feeling of trust and translate into worries about the management of digital data by both public / private entities and specific categories of individuals. In particular, we focused on the respondents’ concerns towards handling practices of private companies, the State, friends or family, strangers, and the employer. Taken together, the mean value of the respondents’ worries, measured by a worry index (range from 0 to 10), is 5.2. This seems to highlight that, overall, the people’s concerns are not very critical.

However, if we look at each specific entity/individual (Graph 2), we find that respondents are more worried about personal data management by strangers (63.6% are “somewhat” or “a lot” worried) and private companies (63.5% are “somewhat” or “a lot” worried), while they are less worried about digital data handling behaviors of friends or family (63.3% are “just a little” or “not at all” worried) and the employer (55.3% are “just a little” or “not at all” worried). Findings on worries about private companies are in line with the low mean value measured on the trust index: the less trust, the greater concern.

document

Visualizing Surveillance Capitalism through Twitter

Introduction

A major issue when dealing with surveillance capitalism is that of visibility. In fact, more than a simple technology per se, surveillance capitalism is rather a complex socio-technical system aimed at extracting data from citizens, along with value embedded in such data. On the one hand, on a technical side, such process of data extraction is largely invisible since it is enacted by an inextricable network made by a multiplicity of devices, platforms, infrastructures and business intermediaries (e.g., data brokers, data vendors, data suppliers, data analysts, etc.). On the other hand, from a cultural perspective, data extraction can be deemed invisible since it is an ‘always-on’ process playing out within users’ everyday digital practices, activities and navigation - and so very difficult to be seen and perceived by citizens.

Therefore, we asked ourselves whether and to what extent surveillance capitalism can be made visible as well as whether and to what extent one can visualize people’s imaginaries of surveillance capitalism. To try answering this question we turned to Twitter and the countless digital traces users leave behind on the platform - traces that we captured and explored with ad hoc data visualization techniques.

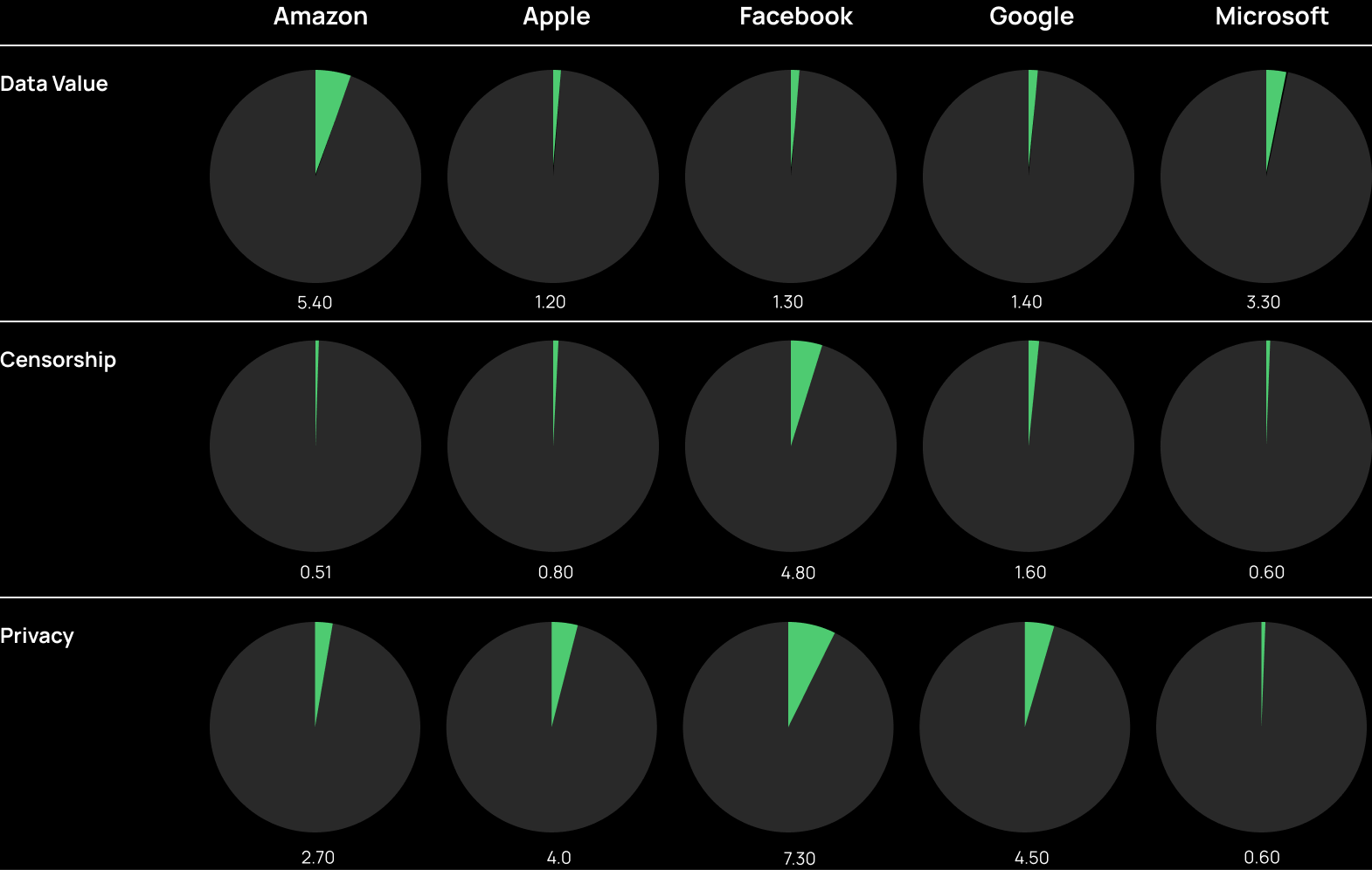

Specifically we collected 1,260,467 tweets from 01/01/2019 to 01/01/2022 (written in Italian), by following these five keywords: ‘Google’, ‘Amazon’, ‘Facebook’, ‘Apple’, ‘Microsoft’ - (aka GAFAM, the five champions of surveillance capitalism). Then, we submitted the dataset to two different kinds of analysis, which, in turn, generate two different visual outputs.

Output 1

After a thorough manual analysis of the tweets, we identified three main categories that capture the key topics typically associated with surveillance capitalism: data value (e.g. tweets dealing with matters of advertising or financial market); censorship (e.g., tweets dealing with pieces of content or users banned by a certain platform); privacy (e.g., tweets dealing with issues of data protection). Then we instructed a classifier to automatically identify those topics in the whole dataset.

The visualization displays the distribution of the categories (in %) across the five platforms.

From the visualization above, it is possible to get two main insights. First, on the whole dataset, discourses about data value, censorship, and privacy are minoritarian. When tweeting about GAFAM, users tend to focus on other topics rather than surveillance capitalism. This result confirms a general lack of awareness and interest regarding questions of big data value, extraction, exploitation, protection, breach, management, etc. - which is largely documented by the current academic literature. Second, it is interesting to notice how different platforms score differently according to the topic taken into consideration; specifically: a) Amazon attracts most of the tweets focusing on economic themes (probably given its explicit business vocation); b) Facebook seems to be associated with censorship issues (probably due to the several ‘scandals’ related to content moderation that affected the company over the last few years); c) all platforms seem to raise concerns about privacy and data protection. This last result echoes another well-known insight within the academic literature: when reflecting on the value of their own digital data, people tend to focus on individual forms of value (such as privacy), rather than collective ones (such as economic value).

Output 2

From the whole dataset we extracted a sample of 250 most recurrent hashtags, which we manually assigned to 8 categories: data value (e.g., #ads), privacy (e.g., #cybersecurity) censorship (e.g.,#trumpbanned), platform (e.g., #facebook), news (e.g., #news), politics (e.g., #conte), covid (e.g., #contacttracing).

This visualization is particularly interesting because it allows (so to speak) to ‘make visible’ the users’ imaginary about surveillance capitalism as well as observe the devices, procedures, operators, and conditions that, in their view, enforce the process of data extraction, appropriation, and exportation. In this sense, emblematic are some hashtags associated with the category ‘privacy’, such as: #smartphone, #cookie, #hacker, #spyware, #tracking, #smartglasses. The same goes for some hashtags related to the category ‘data value’, which indicate the means through which platforms monetize digital data: #marketing, #advertising, #trading, #monopoly.

A research project by:

Funded by:

Contact us:

Drop a message to alessandro.caliandro@unipv.it - twitter - facebook - researchgate